Making tracks with veteran snow groomer Ben Finn at the Waterville Valley World Cup

Making tracks with veteran snow groomer Ben Finn

By Roberta Baker, Union Leader Staff, rbaker@unionleader.com

First Published by NH Union Leader, https://www.unionleader.com/

EVER WONDER how ski areas achieve that perfect corduroy snow?

The man to ask is Ben Finn, a professional snow groomer and snowcat operator who travels hemisphere-ranging circuits to doctor slopes and build courses for competitions across the U.S., before heading south for the summer — way south, to forge competition tracks in Australia and New Zealand.

His most recent gig? Building the very exacting double moguls course for the Toyota 2025 Freestyle World Cup at Waterville Valley, which opens Friday. After that, he’ll head to Deer Valley, Utah, to do something similar.

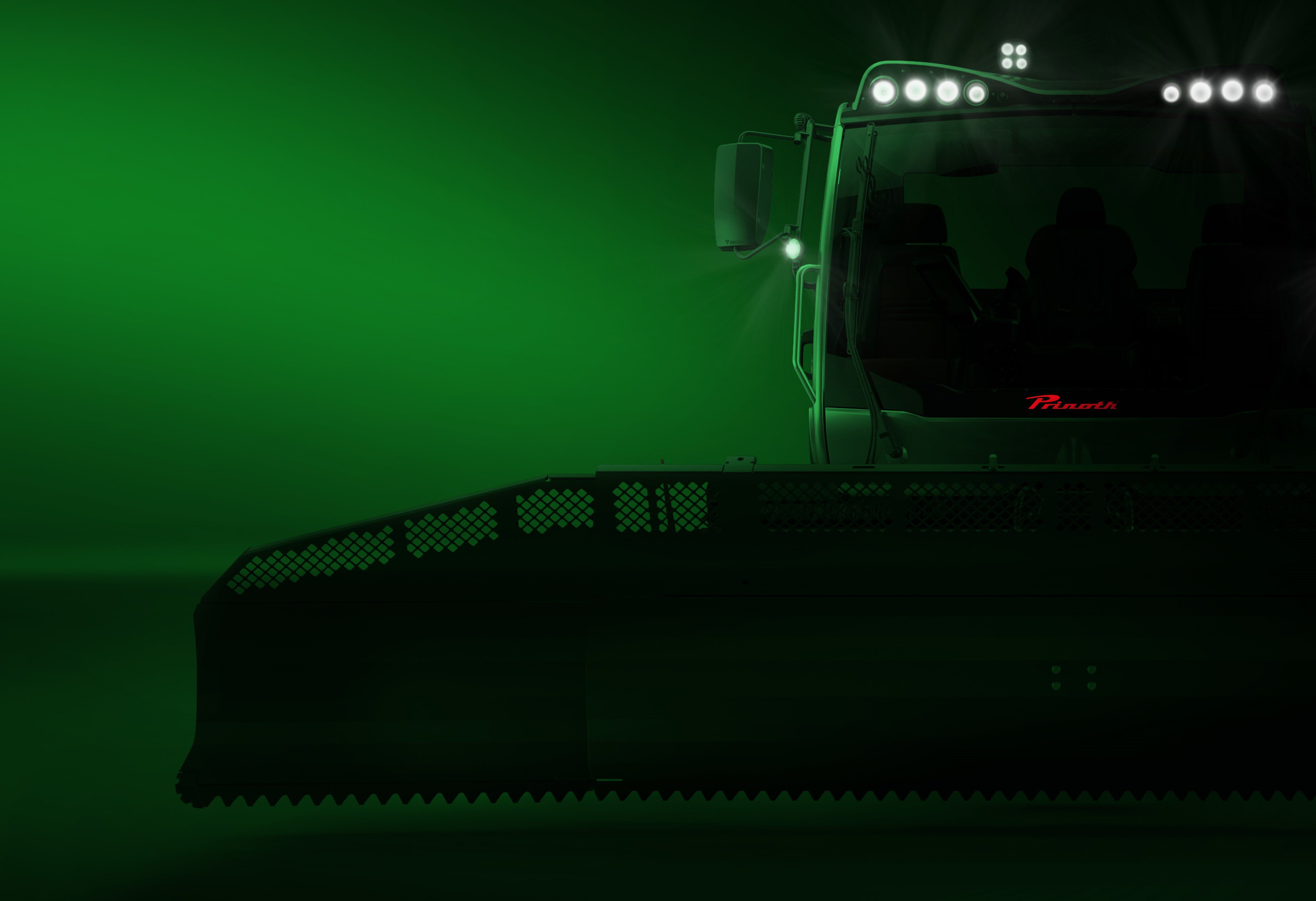

Finn is an expert spreader and carver, a snow sculptor with heavy machinery, seated inside a snow-traveling, slow-going caterpillar. His snowcat is fitted with an 18-foot front blade that moves in 12 directions. “Coming from a ski racing background, I had an obsession for smooth corduroy snow, and I always liked big, heavy equipment,” said Finn, a New England native who belonged to the Black and Blue Trail Smashers, or BBTS, Waterville Valley’s youth ski club.

The inside of his snowcat cab resembles a digital theater, with two screens that constantly measure snow depth, slope angle, and the location and pitch of the machine.

His state-of-the-art model — a Prinoth Bison X — has a winch in the back, with a spool of 1,200 meters of metal cable that anchors the cat to a ridge top. The cable aids traction, particularly in dicey situations on double black-diamond trails, such as Lower Bobby’s Run at Waterville Valley, the site of this year’s championship. The mogul-skiing competition is luring athletes from 18 countries, including Olympic gold medal winners.

A Union Leader reporter was lucky enough to catch a ride with Finn last week to view the course in its earliest stages. A person could see oneself wending down this steep slope on skis in soft spring snow, but not traveling inside a 26,000-pound snow dozer with a knee-to-ceiling windshield that stares down a 30-degree slope resembling a slanting cliff.

Heading uphill in Finn’s snowcat felt like being inside a giant sci-fi ATV trudging upward at turtle speed, aiming for the edge of the atmosphere. Going down, the reporter had her seat belt on and gripped two grab bars. As the the thick metal anchoring cable paid out behind the vehicle (it can hold up to 5 tons), one couldn’t help wondering if this is a snow-lovers’ version of a bungee jump. It was exciting, unnerving and fun. It’s an environment that Finn feels at home in. He’s a trove of information, as well as a professional with a candy maker’s passion and a clockmaker’s attention to detail.

How did he learn to do this?

After mastering the controls (including through online tutorials), “They just throw you into it. You get in and go for it,” he said, riding in the cat’s warm cabin. As his eyes scanned the slope, he listened to the snowcat’s traction and took stock of the surface underneath. “A lot of it is just practice,” he said, learning to read the weather and the texture and quality of snow, which changes daily and sometimes hourly.

One of the challenges in fabricating the World Cup course is that the Lower Bobby’s Run slope has a double fall line, meaning it slants sideways as well as downward. Finn’s task is to move enough snow and spread it so the course is level from side to side. This means part of the slope might have 20 feet of snow, while the main section may have just a couple of feet. Finn’s computer screen indicates snow depth with a changing patchwork of colors. Green means he’s within 6 inches of what the course needs to be.

Making tracks

The mogul course, when completed, will resemble a strip from a foam mattress topper, with perfectly spaced bumps and hollows. Or the inside of a gigantic egg carton.

To make a track for competition, Finn has to create a ribbon of bumps at equal intervals, beginning after a ski jump at the top. After a stretch of moguls, there will be a larger, longer jump, which is the launch pad for the competitors’ most dramatic aerial tricks. The boundaries are plotted in the fall with paint marks on trees and ribbons tied to branches. After that, it’s mostly, but not all, GPS.

“We build the moguls with the cat,” Finn said, as the snowcat hummed downward only to turn around and head back up. “Then the local athletes (from BBTS) come and ski it and ski it and ski it. The height of the moguls is determined by the snow, and the amount of ski traffic they’re able to push through it.”

This course is 246 meters long with an average angle of 28 degrees. It takes 55 to 65 hours of “cat time” to construct, Finn said, and 20 to 25 seconds to ski down, at speeds between 20 and 25 mph. At this point, driving the snowcat has become second nature, he said. “If I get old and go blind, I’ll still be able to drive a snowcat,” said Finn.